William Otton

Essence of Truth

William Otton’s carefully crafted modern art paintings beckon you with their intense and unusual colors, the symmetry of a carefully curated gallery within the painting, and the appeal of strong familiar images. There are paintings-within-a-painting that dialogue with each other (including Matisse, Diebenkorn, Monet, Picasso, and Hopper to name a few), and also newly created vistas. At first they seem serious or even wistful in their formality, then there is some whimsy to be found, and ultimately joy, as the art of experiencing art is celebrated.

“My paintings include the essence of ideas, techniques and styles explored by selected artists of the last century who influenced my understanding about what makes a successful painting. I include those essences while also acknowledging 20th century Modernist reductive conventions focused on the elements of art, the two dimensional surface of the canvas and the exploration of color formed space.”

Otton’s journey as an artist is informed by a lifetime within the world of art as a Doctorate of Art, professor at Texas A&M University, museum director the Laguna Art Museum, the Wichita Center for the Arts, and the Art Museum of South Texas, and once again in the studio as a painter, sharing his lifetime in art.

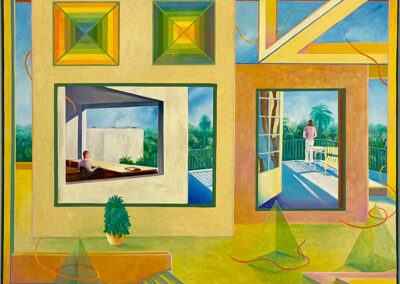

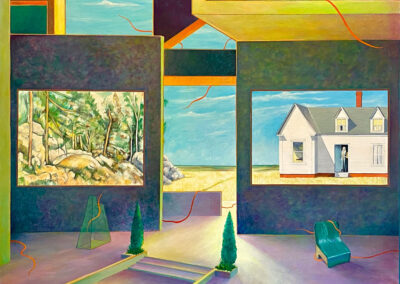

William Otton – Monet to Stella and the Evolution of Pictorial Space – oil on canvas 36″ x 48″ $4500

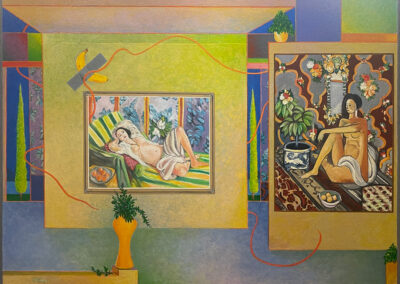

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Diebenkorn and Gauguin Meet in Ingleside – oil on canvas 30″ x 40″ $3500

Based on: “City Landscape #1” Richard Diebenkorn 1963, and “Le Cheval blanc” (The white Horse) Paul Gauguin 1898

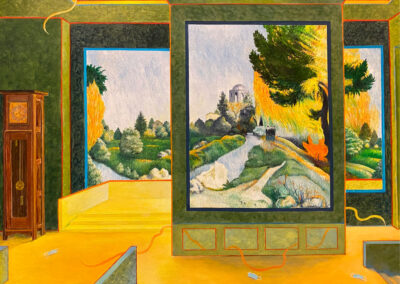

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Gauguin in My Living Room – 24×30 oil on canvas – $2500

Based on Les Alyscamps by Paul Gauguin 1888 aka “Landscape or Three Graces with the Temple of Venus”

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Cezanne and Diebenkorn meet in San Francisco – 36×44 oil on canvas – $4500

Based on – Left: “The Bridge at Maincy by Paul Cezanne” 1879. Right: “Ingleside” by Richard Diebenkorn 1963

William Otton – Essence of Truth – San Francisco Through a Hopper Doorway – 24×20 oil on canvas SOLD

Based on “Stairway” by Edward Hopper 1949

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Memories of Sisley and Hope – 36×36 oil on canvas $3750

Background imagery based on: “Watering Place at Marly” Alfred Sisley 1875

William Otton – The Essence of Truth – Diebenkorn Understands Matisse – 20×24 oil on canvas $1850

Based on – Left: “Ocean Park #79” by Richard Diebenkorn 1975 Right: “A Glimpse of Notre-Dame in the Late Afternoon” by Henri Matisse 1902

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Hopper and Hockney meet in the Tropics – oil on canvas 36″ x 42″ SOLD

William Otton – Bell Mountain Sedona – 24×36 oil on canvas $2750

Based on Mr. Otton’s view out a window in Sedona, Arizona.

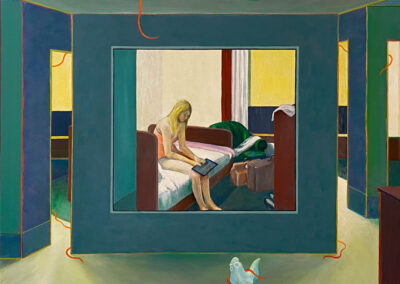

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Hopper at the Seashore – 24×36 oil on canvas $2750

Based on “Excursion into Philosophy Edward Hopper” 1959

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Pissarro Extended Into My Space – 16×20 oil on canvas $1500

Based on “Riverbanks in Pontoise” by Camille Pissarro 1872

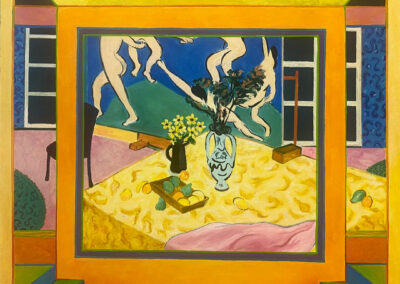

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Diebenkorn Matisse and Bischoff with Norway – 30×40 oil on canvas $3500

Based on – Center: “The Piano Lesson Matisse” 1916. Right: “Ocean Park 16” Diebenkorn, 1968. Top Left: “Girl with Towel” Bischoff, 1960. Bottom Left: Original image by Mr. Otton

William Otton – Walk Along the Bay Trail – 30×40 oil on canvas $3500

Inspired by Mr. Otton’s walks along the Bay Trail in Novato, CA

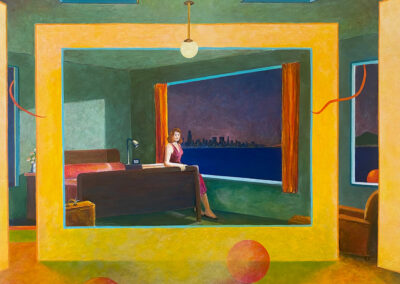

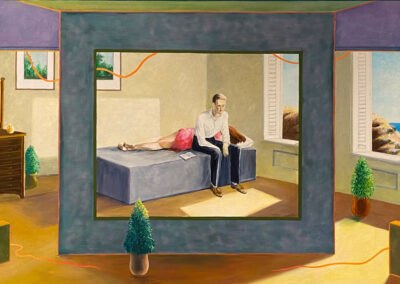

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Hopper During Covid – 24×30 oil on canvas $2500

Based on “Hotel Room” Edward Hopper 1930

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Sisley on My Mind II – 22×28 oil on canvas $2250

Based on “Route de Sèvres near Louveciennes” Alfred Sisley 1873 aka “The Road to the Machine”

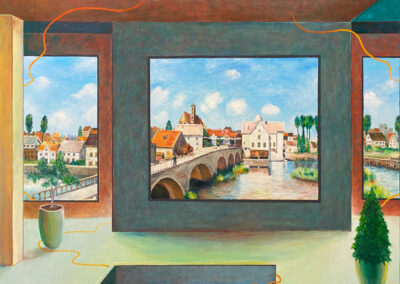

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Sisley Extended at Moret – 24×30 oil on canvas $2500

Based on “The Bridge at Moret” Alfred Sisley 1893

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Slantstep Found with Cezanne and Hopper – 38×48 oil on canvas $4750

Based on – Left: “Forest Interior” Cezanne 1899 Right: “High Noon” Edward Hopper 1949

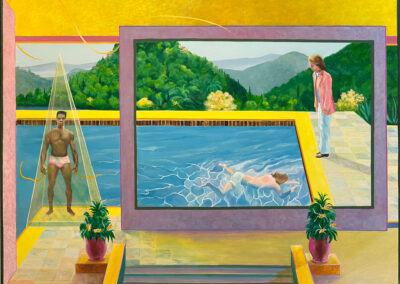

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Three Figures with Pool – oil on canvas 30″ x 40″ $3500

Right: “Two Figures with Pool” David Hockney Left: Original image of swimmer by Mr. Otton, based on AI prompt

William Otton – The Essence of Truth: Extended Monet on a Sunny Afternoon – oil on canvas 26×32 $2750

This painting is patterned after the Claude Monet painting: Argenteuil Basin, 1872. Otton’s goal was to draw on the essence of light and space created by the artist and extend his scene into an imaginary landscape beyond the edges of his original painting. The colors used in the “gallery”, in which I have placed the painting, are influenced by the original Monet work. The formal concerns included in the painting acknowledge the outer edges by using vertical and horizontal lines (the “gallery walls”, steps and ceiling) and the variation of light to dark transitions that help create the illusion of an open space similar to what we see in our visible world. Many of these same conventions are also used in the Monet work.

ARTIST STATEMENT

A Life in Art: History, Inspiration, and the Studio Today

By William Otton September 2025

Introduction: Where Past and Present Meet

Visual art has been at the center of my life for as long as I can remember. From my earliest days in school to decades spent teaching, directing museums, and now painting in my studio, art has been the thread that connects everything I do.Today, as I spend my days creating new work in a vibrant community of artists in Marin County, California, I find myself looking back as much as I look forward.

Art history has always been my guide. The paintings I make today are shaped not only by the world around me but by centuries of innovation that came before. I believe the most meaningful contemporary art is rooted in that lineage—it honors the past, challenges it, and builds upon it.

In 2022, Rachel Murray Meyer, a San Francisco gallerist, visited my studio. Meyer was curious about the ideas driving my work, and our conversation quickly moved beyond technique to the deeper “why” behind each painting. That visit led to a gallery show, a friendship, and an ongoing dialogue about art’s place in a rapidly changing society. It reminded me how essential it is to make art accessible—not just to other artists, but to collectors and viewers who are still learning how to see.

This essay is my attempt to share that journey. It’s a story about how I came to understand art, how I see my role as a painter today, and why I believe art history is still deeply relevant for anyone who creates, collects, or loves art. I also introduce what I believe is the role of collectors as they help identify, purchase, care for, and often provide gifts to public museums as art history unfolds.

My Paintings: Building Conversations Across Centuries

Over the past decade, I’ve made a conscious choice to let the history of Western painting shape my studio practice. Each canvas I create carries echoes of other painters—from the Renaissance to the Modernist era—yet each work is rooted firmly in today’s cultural landscape.

Contemporary art often feels far removed from the formal rules of the past. Many artists today are more focused on social justice, environmental change, identity, and politics than on technical conventions like composition and form. Those concerns are valid and vital; they make today’s art reflective of our times. But I believe history offers an equally rich vocabulary for expression.

My paintings are like conversations: Cézanne, Diebenkorn, and Matisse might all “sit down” together in one piece, their visual languages colliding and reshaping each other, while a detail—a smokestack, a gesture, a window frame—pulls the viewer firmly back into the present. I want each canvas to feel alive, connected to a tradition but unafraid to break from it. Let’s take a closer look at a few examples:

Why History Matters for Today’s Collectors

In a time when art is often viewed as a commodity or a trend, I believe collectors

benefit from understanding art’s lineage. Collecting art isn’t just about buying objects;

it’s about investing in stories, ideas, and connections that enrich your own life.

Art history is full of conversations across time. Renaissance artists borrowed

from classical antiquity. Modernists challenged the Renaissance. Postmodernists

deconstructed Modernism. And now, Contemporary artists remix it all and add their

when set of human concerns into the mix. By referencing earlier painters in my own

work, I invite collectors to participate in that conversation—to own a painting that

acknowledges the past while speaking to the present.

My gallerist understood this when she visited my studio. Her questions weren’t

about technique or price; they were about why I make what I make. She wanted to

understand the stories behind the brushstrokes; the use of art history in the works and

why the use of color seemed so important in the canvases in the studio. I realized that

collectors and individuals, like her – curious, thoughtful, and engaged – are essential to

keeping this dialogue alive as artists and their work move into the public arena.

My Journey: From Beginning in Hawaii to the Studio Today

My connection to art began early, though I didn’t always know where it would

lead me. I was born in Honolulu on June 11, 1939, on King Kamehameha’s birthday—a

day of parades and celebration in Hawaii. Two years later, with World War II intensifying

in the Pacific, I boarded a converted luxury liner bound for Los Angeles with my

grandmother, leaving behind the islands for safety.

By second grade, an encouraging teacher praised a papier-mâché cow I made in

class, and something clicked. I discovered I loved creating things with my hands. My

family moved often up and down California, chasing the American Dream, but art

became my anchor. By high school, I knew I wanted to explore the creative process

seriously.

I enrolled at Chico State University in 1957, choosing art and art education as my

focus. The creative process came naturally, but understanding art as a discipline—a

vast, interconnected web of history, theory, and practice—would take decades of study.

After marriage, two children, and two years teaching in Micronesia, I returned to

California determined to deepen my understanding of art. I earned a Master’s degree at

California State University, Sacramento, exhibiting paintings inspired by the

Photorealism movement of the time. Yet I still felt I was missing something—a deeper

framework to connect my work with the larger story of art.

That’s when I enrolled in a doctoral program at Illinois State University in 1970, a

decision that would shape the rest of my life.

Illinois State University: A Turning Point

The doctoral program at ISU was experimental and bold in design for its time: a

blend of studio practice, art history, and theory designed to prepare graduates to teach

at the university level or lead in art-related fields. My advisor, Dr. Harold Gregor, was a

respected Midwest painter who challenged his students to think deeply about art’s

evolution.

Gregor believed that to understand contemporary art, you had to start at the

beginning—Renaissance Italy, where artists invented new ways of creating space and

depicting reality. He showed us how breakthroughs like perspective and chiaroscuro

transformed painting, setting the stage for every movement that followed.

In his seminars and in my studio critiques, I learned to see painting as a continuum. The

innovations of Masaccio and Leonardo were just as relevant as those of Cézanne or

Pollock because they all formed part of an ongoing exploration of how humans see,

feel, and understand their world.

Those three years at ISU gave me a framework I’ve carried ever since—first intoa teaching career, then into museum leadership, and now into my studio practice. I understood not just how to paint but why painting matters, and how each artist, no matter the era, contributes to a larger cultural dialogue.

A Brief Tour of Art’s Big Shifts

For collectors who are just beginning to explore art, a little history can be a powerful tool. Here is a quick roadmap of how painting evolved and why these shifts still matter today.

Art About Life: From the Renaissance through the 19th century, painting was primarily about telling stories—religious, mythological, historical, or personal. Artists like Raphael, Caravaggio, and Rubens perfected the illusion of depth and form, turning paintings into windows onto another world.

Art About Art: In the late 1800s, Impressionists like Monet began to focus less on narrative and more on the experience of seeing. Cézanne took it further, breaking landscapes into planes of color. By the 20th century, Picasso, Braque, and others abandoned traditional perspective altogether, emphasizing the painting’s structure over its subject. •

Art About Concept: Mid-20th century artists pushed abstraction to its limits, paving the way for Conceptual Art, where the idea itself became the artwork. Duchamp’s Fountain (a urinal displayed as art) is the classic example.

Today’s Contemporary art world blends all three modes. Artists can tell stories, explore materials, or create purely conceptual work—or, like me, they can weave them together.

Museums, Teaching, and Returning to the Studio

My education led me into a career as both teacher and museum director. I directed museums in California, Kansas, and Texas, experiences that gave me a unique perspective on how art is presented and preserved. Working behind the scenes taught me that every artwork has a life of its own, shaped by the people who collect, study, and share it.

Eventually, though, I felt the pull of the studio more strongly than ever. After years of shaping exhibitions and teaching students, I returned to painting full-time, eager to apply everything I had learned. Today, my studio is a laboratory where history and the present moment meet on canvas.

Why Collectors Matter

Collectors play an essential role in this story. Without people willing to support artists, preserve their work, and share it with others, much of art history would have been lost. As a painter, I see collectors not just as buyers but as collaborators—they decide which works will be cared for, which stories will continue to be told.

From my experience as an art museum director and educator I always had the same advice: look at as much art as you can; buy what moves you, but take time to understand its context. Learn why an artist makes the choices they do, and see how their work fits into a larger tradition. Art is more than decoration; it’s a conversation one joins when an object becomes part of your life.

Conclusion: A Living Conversation

Looking back, I realize my life’s work has been about building bridges—between past and present, between artist and collector, between tradition and innovation. My paintings are rooted in the history of Western art, but they’re also responses to our time: a time of political tension, environmental urgency, and rapid cultural change.

Art has always reflected its moment while carrying echoes of the past. My goal is to create paintings that feel timeless yet grounded in today’s world, inviting viewers to slow down, look closely, and see history not as a distant subject but as a living conversation.

For collectors and the general viewer who set aside time to visit fine art in galleries and museums, I hope these works offer more than a visual experience. I Also would like the work to become windows into the story of western art’s history – a reminder that art depicts the values, ideas and important human concerns from the past, while also pointing toward the future.

BIO

William Otton started his career in art as a public school teacher in Paradise, California after graduation from college. He then gained a Masters in Art from Sacramento State where his advisor, Joseph Raffael, and Committee members, Jim Nutt, John Fitzgibbon and other teachers launched him on a professional career in fine art.

He then returned to university and achieved a doctoral degree in Illinois where he studied under midwest regionalist painters, Harold Gregor and Ken Holder, who sent him on the path of leadership in organizations that further fine art in any community in which he lived.

The journey eventually took the form of museum directorships in Laguna Beach, CA, Wichita, KS, Corpus Christi, TX, and Sacramento, CA. Mr Otton now resides Marin County where he has been able to return to studio work.

Review by Dewitt Cheng

WILLIAM OTTON: ESSENCE OF TRUTH

In 1951, the French writer André Malraux introduced the term musée imaginaire in his three-volume work on the psychology of art. In 1965, a portion of that magnum opus was published in English as Museum Without Walls, referring to the expanded world, newly available to art-lovers, that had been created by modern mass communication and photographic reproduction. In the digital age, the proliferation of images far surpasses anything imaginable at mid-century, We are now able to magically summon images and information from all world history to furnish our internet-provenance mental collections.

Malraux’s “museum without walls” comes to mind when we view William Otton’s Essence of Truth paintings of the past seven years. A former museum director and educator who worked during his long career in Texas and California with such art notables as the architect Philip Johnson and the museum founder Eli Broad, Otton moved to the Bay Area after retiring. He resumed painting in earnest, having not exhibited for years, informed by his knowledge of art history, especially the revolutionary art of the twentieth century, which liberated color and form from subservience to the demands of realism, altering modern consciousness. Thrilled by the 2017 San Francisco Museum of Art show that traced Henri Matisse’s influence on Richard Diebenkorn, Otton began painting his Essence of Truth series, an homage to what the artist calls the “vocabulary” of modernism. “Essence” and “truth” are notions that have fallen into disfavor in current art culture, suspicious of tradition and influence. Otton uses the terms in a personal sense (as Cézanne often prefaced his remarks with pour moi, for me), reminding us that good art contains its makers’ subjective truths, which are more compelling—and universally compelling—than art based on dogmatic adherence to received wisdom.

Otton’s paintings within paintings are indeed compelling to lovers of Matisse and Diebenkorn, along with lovers of Pissarro and Sisley; Gauguin and Munch; and O’Keefe and Hopper. These artists’ works are depicted as installed within spare, modernist interiors, museums with some walls replaced by large windows offering views of nature taken from the artist’s hikes on the Novato Bay Trail, and his travels to Arizona, Norway and, Egypt; at times the paintings are extrapolated or “extended,” to use the artist’s term, into the window views, as if invading reality. Paintings that depict other paintings are not new in art history: the eighteenth-century painter Giovanni Paolo Panini depicted colossal art galleries with their walls packed with Roman architectural paintings not unlike his own. David Teniers the Younger and Samuel F.B. Morse (yes, the inventor of the telegraph) followed suit with painstaking paintings of large, teeming galleries in 1647 and 1831, respectively. In modern times, the Italian Giorgio di Chirico depicted artworks and artifacts —classical sculptures, maps, charts, signs— placed inside his “metaphysical” interiors, stripped-down versions of classical architecture. Magritte, of course, is the master of the image/reality conundrum, with paintings depicting small canvases resting on easels, and exactly conforming to the landscapes behind and around them.

Otton’s images can be enjoyed without benefit of curator or docent, but their references and allusions are intriguing:

—“The Essence of Truth: “Diebenkorn and Munch at the San Francisco Modern,” the first of the series, depicts a minimalist modern interior of concrete and plaster planes intersecting at right angles, delicately colored with hues taken from the Diebenkorn abstraction on the left. The Alfred Barr: Missionary for the Modern biography precariously perched on the coffee table is an homage to the Museum of Modern Art curator who brought European modernism to America in the 1930s. A translucent border around the edge of the painting reinforces the flat abstract composition enclosing Munch’s temptress (borrowed from the 1894 painting, “Ashes”). Outside, through the door, a seashore beckons, reflected and continued in a small window or mirror.

—In “The Essence of Truth: Diebenkorn Understands Matisse,” a 1975 Diebenkorn Ocean Park series abstraction and a 1902 Matisse landscape of Paris, both featuring cool gray palettes, hang on parallel short walls behind and between which we glimpse the Notre Dame landscape extended from Matisse’s image. The same architectural framework underlies “Essence of Truth: Cézanne and Diebenkorn Meet in San Francisco,” with the painter’s landscapes spilling into the outdoor view behind them. Note the arcades above, borrowed from di Chirico, and the ribbonlike forms—Otton calls them ‘biomorphic,’ using the art-historical term for abstract organic shapes— that float in and out of the windows and before and behind walls, lending animation and contrast to the Mondrianesque opposing horizontals and verticals that reflect and echo the boundaries of the painting.

—“Essence of Truth: Slantstep Found with Cézanne and Hopper” adds a contemporary California touch to this dialogue of French and American painters. The Slantstep was a small wood and linoleum structure of unknown purpose that resembled an armless upholstered chair, though slanted and so impossible for seating. In 1965, the artist William T. Wiley bought it at a Mill Valley thrift store for fifty cents, and then presented it as a humorous gift to his graduate student, Bruce Nauman. It became an object of humorous veneration and inspiration for local artists, and now reposes at the Nelson Gallery of the University of California, Davis.

Some of Otton’s paintings incorporate real-life landscapes and comment on contemporary events. “Essence of Truth: Walk Along the Bay Trail” features the Novato hiking trail where Otton hikes regularly, while “San Francisco Through a Hopper Doorway” presents a deep blue evening view of San Francisco as seen across the water from the East Bay, through a large picture window; more complicated is whether the image of stairs, banister and curtains, all consonant with the view through other windows, is a mirror, window, or painting. “Essence of Hopper During Covid” appropriates the contemplative woman sitting on a bed from Hopper’s 1930 “Hotel Room” as a surrogate for the artist—for all of us—pondering (as her laptop awaits) the pandemic’s closures, disruptions and losses. The ceramic figurine on the floor beneath the painting came from a Japanese temple’s funeral fire pit, abandoned after its use in a memorial ceremony.

The one-point perspective that Otton has borrowed from early Renaissance art provides a flexible framework for the artist’s playful mashups of paintings, windows, and mirrors, and his homage to past—but still present in spirit—art and artists. Essence of Truth reminds us that others preceded us, and that others will succeed us; we need to honor their legacies and create legacies of our own worth passing into the future. Picasso said that once something is art, it stays art. Ben Shahn once cautioned artists against their fear of comparison with the greats of the past; he thought we should see them as whispering friends, urging us on. Museums, culture, painting, and art are not dead as rumored, or even passé, if they live on in our hearts and minds.

1101 Lake Street at 12th Avenue

San Francisco CA 94118

415-750-9955