William Otton

William Otton’s carefully crafted modern art paintings beckon you with their intense and unusual colors, the symmetry of a carefully curated gallery within the painting, and the appeal of strong familiar images. There are paintings-within-a-painting that dialogue with each other (including Matisse, Diebenkorn, Monet, Picasso, and Hopper to name a few), and also newly created vistas. At first they seem serious or even wistful in their formality, then there is some whimsy to be found, and ultimately joy, as the art of experiencing art is celebrated.

“My paintings include the essence of ideas, techniques and styles explored by selected artists of the last century who influenced my understanding about what makes a successful painting. I include those essences while also acknowledging 20th century Modernist reductive conventions focused on the elements of art, the two dimensional surface of the canvas and the exploration of color formed space.”

Otton’s journey as an artist is informed by a lifetime within the world of art as a Doctorate of Art, professor at Texas A&M University, museum director the Laguna Art Museum, the Wichita Center for the Arts, and the Art Museum of South Texas, and once again in the studio as a painter, sharing his lifetime in art.

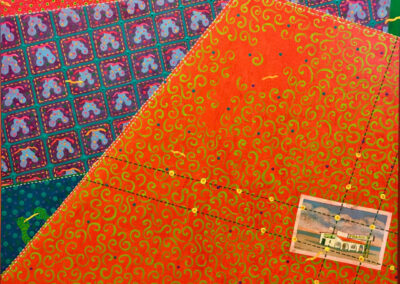

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Diebenkorn and Gauguin Meet in Ingleside – oil on canvas 30″ x 40″ $3500

Based on: “City Landscape #1” Richard Diebenkorn 1963, and “Le Cheval blanc” (The white Horse) Paul Gauguin 1898

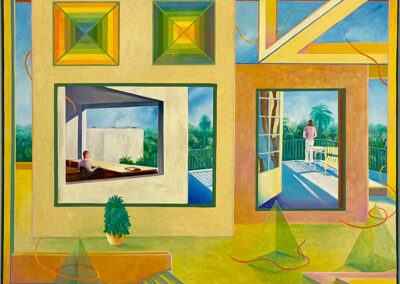

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Hopper and Hockney meet in the Tropics – oil on canvas 36″ x 42″ $4250

Based on: ”Office in a Small City” Edward Hopper 1953, and “Sur la Terrasse” David Hockney 1971. With reference to Frank Stella.

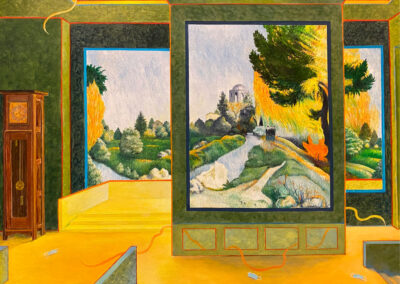

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Gauguin in My Living Room – 24x 30 oil on canvas – $2500

Based on Les Alyscamps by Paul Gauguin 1888 aka “Landscape or Three Graces with the Temple of Venus”

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Cezanne and Diebenkorn meet in San Francisco – 36x 44 oil on canvas – $4500

Based on – Left: “The Bridge at Maincy by Paul Cezanne” 1879. Right: “Ingleside” by Richard Diebenkorn 1963

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Pissarro Extended Into My Space – 16×20 oil on canvas $1500

Based on “Riverbanks in Pontoise” by Camille Pissarro 1872

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Diebenkorn Matisse and Bischoff with Norway – 30×40 oil on canvas $3500

Based on – Center: “The Piano Lesson Matisse” 1916. Right: “Ocean Park 16” Diebenkorn, 1968. Top Left: “Girl with Towel” Bischoff, 1960. Bottom Left: Original image by Mr. Otton

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Diebenkorn and Munch at the San Francisco Modern – 30×40 oil on canvas $3500

Based on Left: “Ocean Park #79” 1975, Richard Diebenkorn. Background inspired by Henri Matisse.

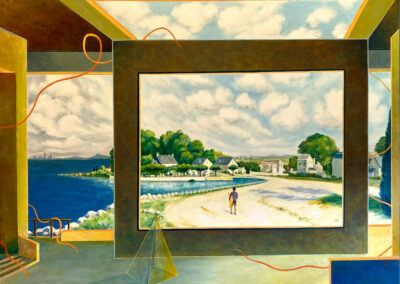

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Memories of Sisley and Hope – 36×36 oil on canvas $3750

Background imagery based on: “Watering Place at Marly” Alfred Sisley 1875

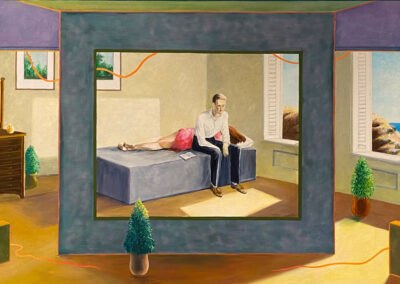

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Hopper at the Seashore – 24×36 oil on canvas $2750

Based on “Excursion into Philosophy Edward Hopper” 1959

William Otton – The Essence of Truth – Diebenkorn Understands Matisse – 20×24 oil on canvas $1850

Based on – Left: “Ocean Park #79” by Richard Diebenkorn 1975 Right: “A Glimpse of Notre-Dame in the Late Afternoon” by Henri Matisse 1902

William Otton – Bell Mountain Sedona – 24×36 oil on canvas $2750

Based on Mr. Otton’s view out a window in Sedona, Arizona.

William Otton – Walk Along the Bay Trail – 30×40 oil on canvas $3500

Inspired by Mr. Otton’s walks along the Bay Trail in Novato, CA

William Otton – Essence of Truth – San Francisco Through a Hopper Doorway – 24×20 oil on canvas $1850

Based on “Stairway” by Edward Hopper 1949

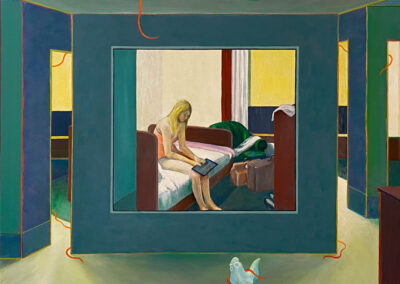

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Hopper During Covid – 24×30 oil on canvas $2500

Based on “Hotel Room” Edward Hopper 1930

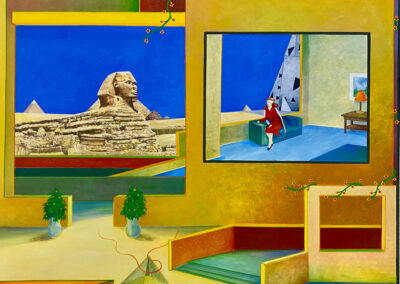

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Hopper Lady Goes to Egypt – 36×42 oil on canvas $4250

Based on “Hotel Window” Edward Hopper 1956.

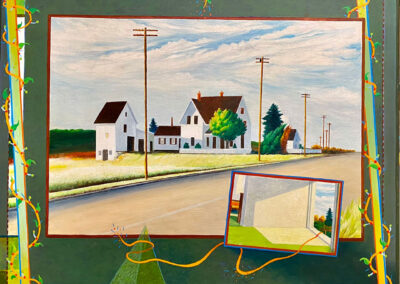

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Revisit to Route 6 Eastham – 30×30 oil on canvas $3000

Main image: “Route 6, Eastham” Edward Hopper 1941 Inset: “Rooms by the Sea” Edward Hopper 1951

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Sisley on My Mind II – 22×28 oil on canvas $2250

Based on “Route de Sèvres near Louveciennes” Alfred Sisley 1873 aka “The Road to the Machine”

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Hopper Woman Looks at Pharaoh Menkaura – 24×48 oil on canvas $3500

Right: “August in the City” Edward Hopper 1945.

Willaim Otton – Essence of Truth – Sisley on My Mind 1 – 28×32 oil on canvas $3000

Based on “The Seine at Port-Marly, Piles of Sand” Alfred Sisley 1875

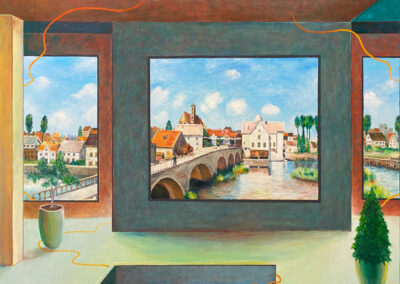

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Sisley Extended at Moret – 24×30 oil on canvas $2500

Based on “The Bridge at Moret” Alfred Sisley 1893

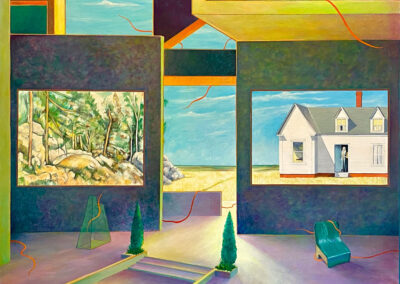

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Slantstep Found with Cezanne and Hopper – 38×48 oil on canvas $5000

Based on – Left: “Forest Interior” Cezanne 1899 Right: “High Noon” Edward Hopper 1949

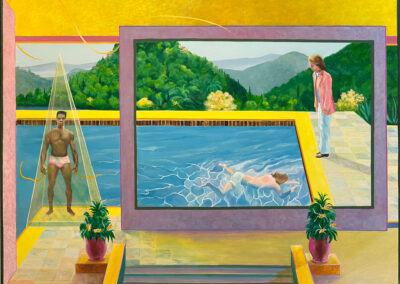

William Otton – Essence of Truth – Three Figures with Pool – oil on canvas 30″ x 40″ $3500

Right: “Two Figures with Pool” David Hockney Left: Original image of swimmer by Mr. Otton, based on AI prompt

William Otton – Bischoff and Rothko Together – 23″ x 30″ Oil on Canvas – SOLD

The color composition in this work draws from the palettes of the two selected paintings. The overall composition is an illusionary gallery that refers to work by Mondrian who used this pure abstract format. Elmer Bischoff, Two Figures at the Seashore, 1957 and Untitled, 1948 (right) Mark Rothko, Number 17, 1949, (left)

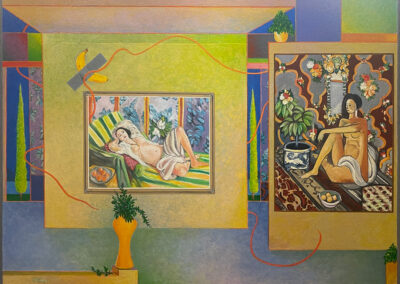

William Otton – Matisse and Diebenkorn in the Gallery – 30″ x 40″ Oil on Canvas – SOLD

Two important works, Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park # 54, 1972 and Henri Matisse, On the Terrace, 1912 are placed in an imagined color structured space using a palette of warm to cool complementary colors. Conceptual window designs for a in a chapel in Vance, France were done by Matisse.

William Otton – Edward Hopper on my Mind – 30″ x 40″ Oil on Canvas – SOLD

Edward Hopper is recognized for his unique narrative paintings that use spare details and color systems that add emotion and impact. Various images by Hopper have been placed in an imaginary gallery with a landscape that is informed by the central painting, Carolina Morning, 1955. left to right: The Long Leg, 1939 Marshall’s House, 1932 Carolina Morning, 1955 Apartment Houses, 1923 Apartment Houses, 1923

William Otton – Cezanne and Diebenkorn Meet Near the Freeway – 30″ x 40″ Oil on Canvas – SOLD

Images found in master artist’s compositions are imagined into a landscape beyond the edges of their depicted works. The freeway and road from Richard Diebenkorn’s, Woman In Profile, 1958 is merged with Paul Cezanne’s, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Bibemus, 1897. The central interior room is based on the work of Mexican architect, Ricardo Legorreta, a follower of the Modernist tradition. It refers to a time when Mr. Otton was working with him to expand the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi, Texas.

William Otton – The Essence of Truth: Matisse Picasso and Diebenkorn Vie for Attention – 30″ x 40″ oil on canvas SOLD

William Otton – The Essence of Truth: Extended Monet on a Sunny Afternoon – oil on canvas 26″ x 32″ Inquire

This painting is patterned after the Claude Monet painting: Argenteuil Basin, 1872. Otton’s goal was to draw on the essence of light and space created by the artist and extend his scene into an imaginary landscape beyond the edges of his original painting. The colors used in the “gallery”, in which I have placed the painting, are influenced by the original Monet work. The formal concerns included in the painting acknowledge the outer edges by using vertical and horizontal lines (the “gallery walls”, steps and ceiling) and the variation of light to dark transitions that help create the illusion of an open space similar to what we see in our visible world. Many of these same conventions are also used in the Monet work.

William Otton – Hopper Woman Looking Out on San Francisco- oil on canvas -27″ x 34″ SOLD

This painting draws from a composition by Edward Hopper, Room in Brooklyn, painted in 1932. The view has been changed to San Francisco Bay with an imaginary fire occurring in Marin County north of the Golden Gate Bridge. The painting acknowledges a 20th century master and focuses on how color systems can enhance a painting. The fact that Hopper included light falling through the window onto the floor created a special challenge when San Francisco was to be featured at night. The illusion of light falling onto a walkway outside the room became the artist’s solution to making the scene make visual sense.

William Otton – Essence of Truth: Diebenkorn and Cezanne Meet in Santa Barbara – oil on canvas 34″ x 40″ SOLD

Richard Diebenkorn’s (Figure on a Porch, 1959) and Paul Cezanne’s (Lac d’Annency, 1896) were the selected artists for this work. The result is an example of my merging the compositions of each artist into a central invented space through the open door and windows in the middle of the composition. The implied “room” in which the paintings are installed, and the open space through the doorway and windows, is based on an interior by Mexican architect, Ricardo Legorreta. The repetition of vertical and horizontal lines is a Modernist concern that brings attention to the picture plane and the bounded edges. They are part of the paintings narrative. In this painting the color and linear elements are the primary elements I use to play an equal role to the representational imagery that makes up the expressive content being conveyed to the viewer.

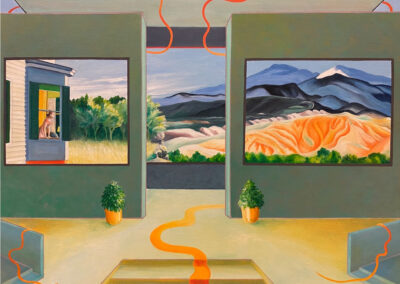

William Otton – Essence of Truth: Hopper and O’Keefe in New Mexico – oil on canvas 24″ x 30″ SOLD

Georgia O’Keefe and Edward Hopper both employed the landscape theme as part of their narratives during their careers. Each artist is admired for their contribution to 20th century art because of the unique way they interpreted the world around them. The “gallery” walls are a repeat of the horizontal and vertical edges of the painting. The walls, floor and ceiling shapes provide an invented location to introduce the images created by the two artists into the composition. Their narratives come together in the middle panel which is invented by extending the images on the left and right sides of the painted gallery space. Thus, the woman in the window is not in New England but has been transported to the rugged landscape of New Mexico. Georgia O’Keefe Edward Hopper Black Mesa Landscape, 1930 Cape Cod Morning, 1950

William Otton – Sisley Goes Surfing Near San Francisco – oil on canvas 31″ x 40″ Inquire

Alfred Sisley’s, (Watering Place at Marly, 1875), is featured in this work. The location begins to rapidly shift when the viewer looks at the created location outside the framed central painting. The clouds from the original composition extend into a much broader space and the “essence” of the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco Bay and city skyline were added. A surfer was added to the original composition.

ARTIST STATEMENT

Background

During the opening years of the twentieth century a new kind of fine art painting emerged in Western European art centers. It was a trend that gained major attention – often controversial – as academic illusionism was being replaced by a new kind of art created by avant-garde artists. These artists rejected the rules demanded by those interested in academic fine art with its focus on representational imagery. Painting was moving into an era where “Art about Art” replaced the emphasis on“Art about Life”.

Art about Life focused on how successfully an artist could dissolve a picture plane and introduce subject matter in a way that often mirrored the visible world and depicted a particular place, event, story or people. The new Art about Art focused on using the elements of art as an important part of the content of a work. It sought to manipulate the surface of the painting, depicting an abstracted kind of imagery as compared to the earlier Art about Life that sought go make images have more verismilitude in a space that mirrored the visible world.

Various movements emerged that continued to further the shift the focus from representational painting toward abstraction and to a flattened picture plane on which loosely painted images might be included such as Cubism. In many cases the brush marks became an important part of the content of a painting as they depicted a new kind of image that was unique to painting.

By the mid 20th century, Action Painting had totally removed any reference to images found in the visible world resulting in a fully abstract format. However, by the later decades of the century artists like Andy Warhol reintroduced representational images into Modern Art and in doing so helped raise the question about the future importance of abstraction.

Today

Since the beginning of the 21st century there has been a focus on issues related to “multiculturalism” across society and efforts to replace what many call the colonial derived “melting pot” outlook of the past with a new way to look at history, current affairs and the future. This new thinking is thought to be the best way for western culture to move forward. Questioning the melting pot approach of past centuries has impacted the development of fine art today. It has also impacted the art history discussed in the above paragraphs which sought a single line of art development including a specific group of artists and an exclusion of diversity and multi points of view.

Yes, a melting pot approach to defining culture and fine art has strong weaknesses. In fine art it includes limited acceptance of works created by women and people of color as well as any major focus on social issues, political points of view and topics that fall outside the parameters of defining what constitutes a masterpiece.

Today multiculturalism has a major impact on what artists create in their studios and how art history is being rewritten to better serve this new way of looking at culture. As these changes occur there is are efforts in some art circles to discount the fine art developments of the last 150 years and replace it with a new view of what actually happened from a multicultural point of view and discounting many of the contributions that were accepted as valid in the past.

Since 2015, when multiculturalism became a dominant influence on contemporary art making I shifted my outlook about how I viewed what was happening in fine art. I sought a way to keep the major threads of art history alive by addressing it in some way in my own works. My solution was to include the “essence” of past works into my own studio efforts.

Today my paintings include the essence of ideas, techniques and styles explored by selected artists of the last century who influenced my understanding about what makes a successful painting. I include those essences while also acknowledging 20th century Modernist reductive conventions focused on the elements of art, the two dimensional surface of the canvas and the exploration of color formed space.

Unlike many leading abstract artists of the last century I have never dropped the recognizable image from my work, no matter how abstracted it might be in a painting. I also believe that including the conventions that are part of the Modernist vocabulary can and should be integrated into my paintings. The current work seeks to successfully blend the conventions of Modernism and my interest in representational image making into each painting I create in my studio.

BIO

William Otton started his career in art as a public school teacher in Paradise, California after graduation from college. He then gained a Masters in Art from Sacramento State where his advisor, Joseph Raffael, and Committee members, Jim Nutt, John Fitzgibbon and other teachers launched him on a professional career in fine art.

He then returned to university and achieved a doctoral degree in Illinois where he studied under midwest regionalist painters, Harold Gregor and Ken Holder, who sent him on the path of leadership in organizations that further fine art in any community in which he lived.

The journey eventually took the form of museum directorships in Laguna Beach, CA, Wichita, KS, Corpus Christi, TX, and Sacramento, CA. Mr Otton now resides Marin County where he has been able to return to studio work.

Review by Dewitt Cheng

WILLIAM OTTON: ESSENCE OF TRUTH

In 1951, the French writer André Malraux introduced the term musée imaginaire in his three-volume work on the psychology of art. In 1965, a portion of that magnum opus was published in English as Museum Without Walls, referring to the expanded world, newly available to art-lovers, that had been created by modern mass communication and photographic reproduction. In the digital age, the proliferation of images far surpasses anything imaginable at mid-century, We are now able to magically summon images and information from all world history to furnish our internet-provenance mental collections.

Malraux’s “museum without walls” comes to mind when we view William Otton’s Essence of Truth paintings of the past seven years. A former museum director and educator who worked during his long career in Texas and California with such art notables as the architect Philip Johnson and the museum founder Eli Broad, Otton moved to the Bay Area after retiring. He resumed painting in earnest, having not exhibited for years, informed by his knowledge of art history, especially the revolutionary art of the twentieth century, which liberated color and form from subservience to the demands of realism, altering modern consciousness. Thrilled by the 2017 San Francisco Museum of Art show that traced Henri Matisse’s influence on Richard Diebenkorn, Otton began painting his Essence of Truth series, an homage to what the artist calls the “vocabulary” of modernism. “Essence” and “truth” are notions that have fallen into disfavor in current art culture, suspicious of tradition and influence. Otton uses the terms in a personal sense (as Cézanne often prefaced his remarks with pour moi, for me), reminding us that good art contains its makers’ subjective truths, which are more compelling—and universally compelling—than art based on dogmatic adherence to received wisdom.

Otton’s paintings within paintings are indeed compelling to lovers of Matisse and Diebenkorn, along with lovers of Pissarro and Sisley; Gauguin and Munch; and O’Keefe and Hopper. These artists’ works are depicted as installed within spare, modernist interiors, museums with some walls replaced by large windows offering views of nature taken from the artist’s hikes on the Novato Bay Trail, and his travels to Arizona, Norway and, Egypt; at times the paintings are extrapolated or “extended,” to use the artist’s term, into the window views, as if invading reality. Paintings that depict other paintings are not new in art history: the eighteenth-century painter Giovanni Paolo Panini depicted colossal art galleries with their walls packed with Roman architectural paintings not unlike his own. David Teniers the Younger and Samuel F.B. Morse (yes, the inventor of the telegraph) followed suit with painstaking paintings of large, teeming galleries in 1647 and 1831, respectively. In modern times, the Italian Giorgio di Chirico depicted artworks and artifacts —classical sculptures, maps, charts, signs— placed inside his “metaphysical” interiors, stripped-down versions of classical architecture. Magritte, of course, is the master of the image/reality conundrum, with paintings depicting small canvases resting on easels, and exactly conforming to the landscapes behind and around them.

Otton’s images can be enjoyed without benefit of curator or docent, but their references and allusions are intriguing:

—“The Essence of Truth: “Diebenkorn and Munch at the San Francisco Modern,” the first of the series, depicts a minimalist modern interior of concrete and plaster planes intersecting at right angles, delicately colored with hues taken from the Diebenkorn abstraction on the left. The Alfred Barr: Missionary for the Modern biography precariously perched on the coffee table is an homage to the Museum of Modern Art curator who brought European modernism to America in the 1930s. A translucent border around the edge of the painting reinforces the flat abstract composition enclosing Munch’s temptress (borrowed from the 1894 painting, “Ashes”). Outside, through the door, a seashore beckons, reflected and continued in a small window or mirror.

—In “The Essence of Truth: Diebenkorn Understands Matisse,” a 1975 Diebenkorn Ocean Park series abstraction and a 1902 Matisse landscape of Paris, both featuring cool gray palettes, hang on parallel short walls behind and between which we glimpse the Notre Dame landscape extended from Matisse’s image. The same architectural framework underlies “Essence of Truth: Cézanne and Diebenkorn Meet in San Francisco,” with the painter’s landscapes spilling into the outdoor view behind them. Note the arcades above, borrowed from di Chirico, and the ribbonlike forms—Otton calls them ‘biomorphic,’ using the art-historical term for abstract organic shapes— that float in and out of the windows and before and behind walls, lending animation and contrast to the Mondrianesque opposing horizontals and verticals that reflect and echo the boundaries of the painting.

—“Essence of Truth: Slantstep Found with Cézanne and Hopper” adds a contemporary California touch to this dialogue of French and American painters. The Slantstep was a small wood and linoleum structure of unknown purpose that resembled an armless upholstered chair, though slanted and so impossible for seating. In 1965, the artist William T. Wiley bought it at a Mill Valley thrift store for fifty cents, and then presented it as a humorous gift to his graduate student, Bruce Nauman. It became an object of humorous veneration and inspiration for local artists, and now reposes at the Nelson Gallery of the University of California, Davis.

Some of Otton’s paintings incorporate real-life landscapes and comment on contemporary events. “Essence of Truth: Walk Along the Bay Trail” features the Novato hiking trail where Otton hikes regularly, while “San Francisco Through a Hopper Doorway” presents a deep blue evening view of San Francisco as seen across the water from the East Bay, through a large picture window; more complicated is whether the image of stairs, banister and curtains, all consonant with the view through other windows, is a mirror, window, or painting. “Essence of Hopper During Covid” appropriates the contemplative woman sitting on a bed from Hopper’s 1930 “Hotel Room” as a surrogate for the artist—for all of us—pondering (as her laptop awaits) the pandemic’s closures, disruptions and losses. The ceramic figurine on the floor beneath the painting came from a Japanese temple’s funeral fire pit, abandoned after its use in a memorial ceremony.

The one-point perspective that Otton has borrowed from early Renaissance art provides a flexible framework for the artist’s playful mashups of paintings, windows, and mirrors, and his homage to past—but still present in spirit—art and artists. Essence of Truth reminds us that others preceded us, and that others will succeed us; we need to honor their legacies and create legacies of our own worth passing into the future. Picasso said that once something is art, it stays art. Ben Shahn once cautioned artists against their fear of comparison with the greats of the past; he thought we should see them as whispering friends, urging us on. Museums, culture, painting, and art are not dead as rumored, or even passé, if they live on in our hearts and minds.

1101 Lake Street at 12th Avenue

San Francisco CA 94118

415-750-9955